Art and life were once two separate things, but the more and more art developed, the closer those two things became. The avant-garde art is about bringing art and life together - art that pushes the boundaries integrates art and life sometimes without even realizing it.

Rauschenberg's "Bed" is a lovely example of exactly this idea because he literally took his pillow, sheets and quilt and painted directly on those items. Then he hung it vertically in a gallery on display for all to see. He created his art out of thing in his life - thus bringing together art and life into one thing.

Rauschenberg was part of this Neo-Dada art movement, in which his "Bed" artwork was a rejection of what's called "indexical trace." Indexical trace is not unlike what we refer to as "painterly strokes" meaning that within an artwork you can tell where the artist has been. Look at Jackson Pollock's work - any of it really - and you can see where his arm moved with the brush stroke, and then in his later and more famous paintings, you can see the places in which he stood and walked around the canvas dropping a paint trail as he went. De Kooning is also a wonderful example, because his brush strokes are very pronounced in all of his artworks. You can see exactly where he moved his hand and arm while he was creating his masterpieces.

But Rauschenberg was so not all about being able to see where his brush stroked the canvas, he wanted to leave those ideas behind and do something different.

Greenberg was about many things - and some of those things being abstract painting and non-representational paintings done on a flat surface and not made to be something they weren't. A lot of artists really hated Greenberg and what he brought to the table, and in the 60s they started to fully reject what this "great" critic had to say about art and his idea of what good art should be.

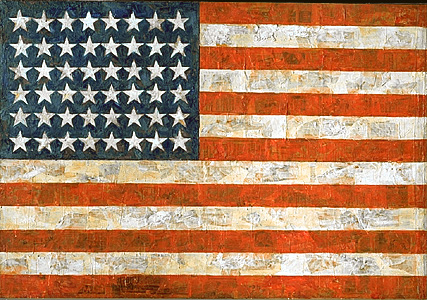

Rauschenberg isn't the only one who rejected Greenberg's ideas by making jokes out of what was said about good art. Jasper Johns rejected Greenberg's "rules" also and openly and defiantly applied Greenberg's rules to his painting "Flag."

Flags are abstract pieces of art printed on fabric most of the time, and they are non-representational. We only know what the thirteen stripes and fifty stars of the American flag represent because that's what someone told us they are there for. But really, there aren't stars on the American flag - it's a rendition of a star, but really just triangle-y lines in an abstract sort of shape.

And Johns also didn't leave behind brush strokes in his work, it's just smooth right there on the canvas.

The point being, that Greenberg's rules about abstraction and non-representation are crap and they can't be applied to everything like Greenberg would have you believe. Essentially, the "Flag" painting is a big joke. A big middle finger from the art world to Mr. Clement Greenberg.

This attitude took on new faces as more and more artists banded together on this idea of rejecting traditional ways of going about creating "art." Because of what we know about art now, we can look back at the history of art and say "Of course this was going to happen! Just look at what those artists were doing!" When in fact, this is a mis-use of history. Lots of different things could have happened, and if we get into the origins of modernism in architecture we can talk about Lebrouste and the use of iron in buildings and all sorts of things that were considered dead ends, but led into another way of doing things that helped to advance the world of art and architecture. But that's really a whole different issue.

But you see my point.

And it wasn't just the rejection of Greenberg that influenced the advancement of art either, it was also artists like Claes Oldenburg and his crazy pieces of public 'pop' art that helped get art back to being joined with life. His work "The Store" done in 1961 helped bring art and life together in a way that hadn't really been done before.

He created things that we use every day, things that we buy in stores and made out of paper and paint. He was effectively creating a store without actually creating a store. By doing this, he was shoving the idea of kitsch and the avant-garde together in one place.

He said something very profound about art and artwork as well. Adorno was really into autonomous art, and making art be separate from society, but in fact Oldenburg took that idea and transformed it by making art that was part of the society, art that fought with society, but instead of buckling under the pressure of society his art would emerge on top and beat out all that other crappy art.

"I am for an art that is political-erotical-mystical, that does something other than sit on its ass in a museum.

I am for an art that grows up not knowing it is art at all, an art given the chance of having a staring point of zero.

I am for an art that embroils itself with the everyday crap & still comes out on top.

I am for an art that imitates the human, that is comic, if necessary, or violent, or whatever is necessary.

I am for an art that takes its form from the lines of life itself, that twists and extends and accumulates and spits and drips, and is heavy and coarse and blunt and sweet and stupid as life itself."

-Claes Oldenburg "I am for an art" 1961

And then folks, I got to thinking about what all of this means. Art takes on a life of its own. It develops and regresses and it changes and different people do different things. You can't control art, you can't take art away, and you can't ignore art.

Art stares you in the face, wherever you go it's always there. It looks at you, emotes you, provokes you, offends you, hates you, judges you, loves you, hands you everything and takes it all away again. But it does effectively one thing - art is philosophical and conceptual and it is, in fact, tied in very closely with life even though it wasn't always that way.

No comments:

Post a Comment